When the ICO declines to adequately enforce its own rulings, it leaves requesters in a regulatory no-man’s land, undermining their rights to access information.

Unlike in other countries, where requesters can pursue legal remedies directly, in the UK, requestors are almost entirely reliant on the ICO to uphold their information rights.

On the one hand, this makes enforcing one’s information rights in the UK accessible for all.

You don’t have to spend thousands of pounds on lawyers to enforce your rights, as you would have to do in the US and other jurisdictions.

That in practice limits the ability to make requests and get meaningful disclosures to well-funded media organisations and campaign groups, and the wealthy.

On the other hand, the UK approach sometimes makes enforcing timely disclosure more challenging.

One cannot simply take a public body to court if it misses a deadline, one has to go through the ICO, and that takes time.

The worst of the crippling case backlog that developed under previous Information Commissioner Elizabeth Denham has been cleared, and John Edwards’s policy to prioritise cases with the highest public interest has reduced the chance that time sensitive cases are lost in the caseload.

But the ICO still struggles to enforce against public bodies who just refuse to play ball, after it finds in a requestor’s favour.

When the ICO issues a decision notice, which mandates a public body to disclose a piece of information after an appeal against a wrongful refusal, and the public body complies the system has worked.

If the ICO rules against and you think it got the decision wrong, you can appeal to the First Tier Tribunal, and a judge will rule on your case, albeit after some delay.

These hearings are straightforward, and as long as you spend a bit of time working on your public interest arguments, you can represent yourself easily.

But what happens when a public body doesn’t really comply with a decision notice?

Maybe it doesn’t do a proper search of its records and claims it has only limited records. Or maybe it claims a document isn’t in scope when it definitely is.

You go back to the ICO and complain. But sometimes the ICO won’t then take the action one might expect it to enforce the public right to know.

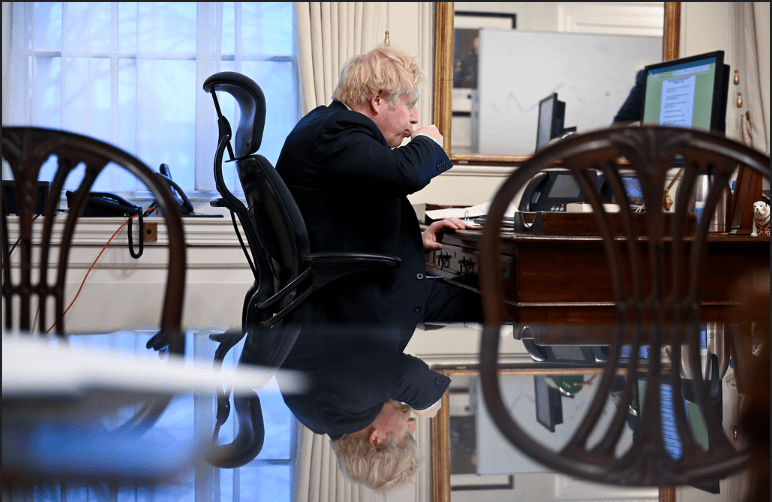

I experienced this recently with a request I made about messages between Boris Johnson and Evgeny Lebedev concerning the media tycoon’s peerage.

This appointment sparked controversy at the time. I asked for a copy of any messages between Johnson and Lebedev on WhatsApp about the peerage.

The ICO upheld my appeal, asking for the Cabinet Office to arrange for a search of Johnson’s phone, after months of delays.

And that’s where the case has ended.

The Cabinet Office, after much cajoling, wrote to Johnson asking for him to complete a search of his phone for any records in the scope of the request.

They say they got no response. The ICO wrote to me saying that was the end of the matter.

I argued that they had not taken appropriate steps to enforce Cabinet Office compliance with the decision notice.

Even though Johnson is now out of office, messages sent in the course of government business remain subject to FOI. If they exist, they are owned by the department and should be disclosed unless exempt.

The ICO said it considered the Cabinet Office had complied with its notice, and that the Cabinet Office contacting Johnson to ask for a search was sufficient, even if they appear to have received no reply.

If the ICO had refused my appeal, ironically, I would perhaps have been in a better legal position. I could have taken the matter to tribunal, and put my case to a judge, who could have issued directions with stronger legal force.

But under the rules, to go to the tribunal, I need a decision notice to dispute. And in this case, the decision notice ruled in my favour, so I have nothing to bring to it.

The only route of appeal in this case would be an expensive judicial review of the ICO’s decision not to enforce its notice.

Unfortunately, news organisations can only afford to do that in certain cases, especially when the request was for WhatsApps which may never have been sent.

In this case, the outcome is that I have simply been unable to enforce my information rights.

But it is not the first time I’ve had trouble with this.

The Attorney General’s Office has failed to respond to an order to disclose material related to its handling of my request for the number of times Suella Braverman forwarded government emails to her private email accounts, despite a decision notice ordering it to respond.

After an 18-month transparency battle, I was finally able to reveal this week she had forwarded correspondence to her private accounts on 127 occasions, which risked breaching the ministerial code.

Given the extensive delays, I wanted to see how the request was handled.

The ICO has the power to certify this failure to comply with a notice as a contempt of court.

It hasn’t yet done this, arguing that the AGO say they missed the email notifying them of the decision notice and allowing them more time to respond.

It has now been 114 days, when normally a public body must respond within 35. It would seem reasonable now to certify the AGO’s non-compliance at this stage.

In another case, I took the Metropolitan Police to the ICO asking for a copy of its “problem profile” concerning violence against women.

These internal performance analysis documents set out where a police force is struggling.

The ICO ruled in my favour, but the Met then took the case to the information tribunal at significant public expense (with its in-house lawyers spending 144 hours on the case excluding external counsel).

Shortly before the hearing was supposed to take place, the Met disclosed much of the document.

I used that to report to reveal police officers had routinely failed to record basic details about sex offenders and their victims, despite repeatedly being told by regulators that its methods are failing women and girls.

But the Met is still trying to withhold significant parts of the document.

The ICO argued disclosure of the redacted document was sufficient, despite the decision notice ordering the whole document to be released. It declined to defend its decision notice further.

We are awaiting an Upper Tier Tribunal decision on this, adding additional months of delays, and leaving the documents less valuable when they are eventually released.

These are just a few of the cases I’ve experienced where the ICO appears to lose the appetite to enforce after it issues a decision notice.

That makes it much harder for those for whom FOI is a crucial tool to use it effectively, even for clear public interest requests such as those detailed above, submitted as part of my public watchdog role as an investigative reporter.

The ICO has made significant improvements recently, pulling back from the brink of severe process delays making FOI unenforceable, and I want to see that process continue.

But unless the ICO takes a more sceptical view of departments who routinely demonstrate their disdain for FOI and steps up enforcement, by certifying failures to comply with decision notices more often and assessing whether public bodies are really complying with decision notices, its ability to enforce accountability is unlikely to improve.

A decision notice without enforcement is not just pointless—it erodes trust in the very system meant to guarantee transparency.

Picture credit: Andrew Parsons / No 10 Downing Street

Leave a comment