Journalists often get the feeling that their FOI is being treated differently.

It may be something which should be straightforward that suddenly takes months.

It might be getting a phone call from a press officer despite having not approached the department for comment yet, or finding material being withheld on consistently flimsy grounds despite an obvious public interest.

A key principle of FOI requests is that they should be handled in an “applicant blind manner”.

A request from Sue Smith of Tunbridge Wells about her bin collection times should be treated in the same manner as one from a seasoned journalistic digger.

Handling should be about the objective public interest in the information being public, not whether the content is planned to be used to commit an act of journalism.

This is often not how things work in practice. The results of a number of subject access requests I have made to government departments have clearly evidenced this.

Everyone has a right to make these requests, and require a department to provide all the information it holds about you. These requests can be really helpful in seeing how your engagements with government are being treated behind closed doors.

References in Cabinet Office emails to me as “the ever-active Mr Greenwood”, and in Department for Health and Social Care emails as “a serial requestor across the whole of government” who will “be quick to criticise us if we leave ambiguity”, are among the most stark breaches of the applicant blind principle I have seen to date.

And my experience is far from unique among reporters.

Braverman’s private email usage

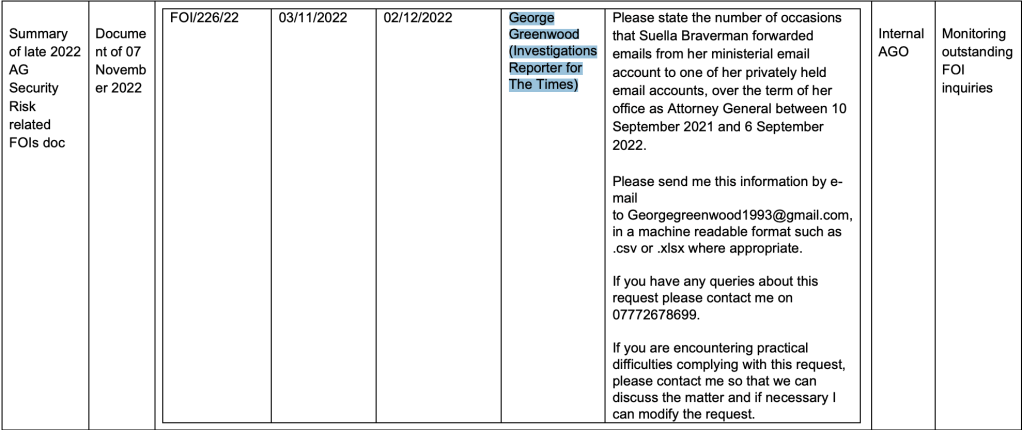

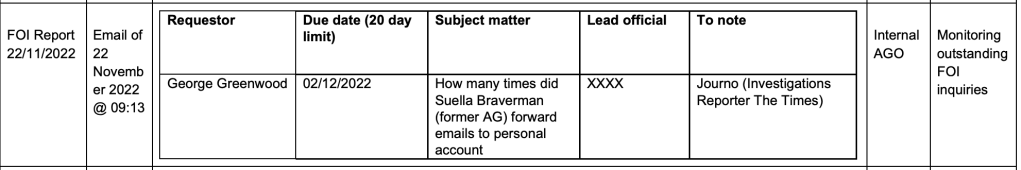

The way in which a request I made to the Attorney General’s Office (AGO) about Suella Braverman’s use of private emails whilst in ministerial office has to win some sort of award for being handled in the least applicant blind manner possible.

For the last couple of years, I have been trying to establish how widespread former Home Secretary Suella Braverman’s use of private emails in office was.

The forwarding of sensitive documents to a private email address risks breaching the ministerial code due to the generally weaker security measures in place on these kinds of email accounts.

Decision making away from government records also creates a democratic deficit by making it harder to hold them accountable by reducing the chance this information will ever be disclosed.

Braverman was forced to resign by Liz Truss in October 2022 for inappropriately using her private email account to send out sensitive documents while in post, before being reappointed to the same role by Sunak.

This struck me as potentially a pattern of behaviour.

So I filed an FOI to the AGO her previous department, to try and identify the number of times it could find in which Braverman forwarded department emails on to a private account.

Two year wait

To even establish that she had forwarded correspondence on to a private account, required more than a year, and two complaints to the transparency regulator, the ICO, including one because the department failed to respond to the request.

To get the number of occasions, it took a court judgement.

It finally emerged that she had forwarded emails account on 127 occasions, which a top cyber security expert said posed a “clear vulnerability”.

When challenged by Nick Ferrari on the story in a radio interview, claimed she just needed to forward the emails to her private account so she could view documents on a split screen on her private laptop, which she claimed she could not do on her ministerial device.

The delays in responding to my initial request, and then the refusal to respond in full after one ICO decision notice, which required a further appeal, struck me as odd, given that all this request required was a relatively simple search of her preserved email account.

So I filed a subject access request.

“Journo”

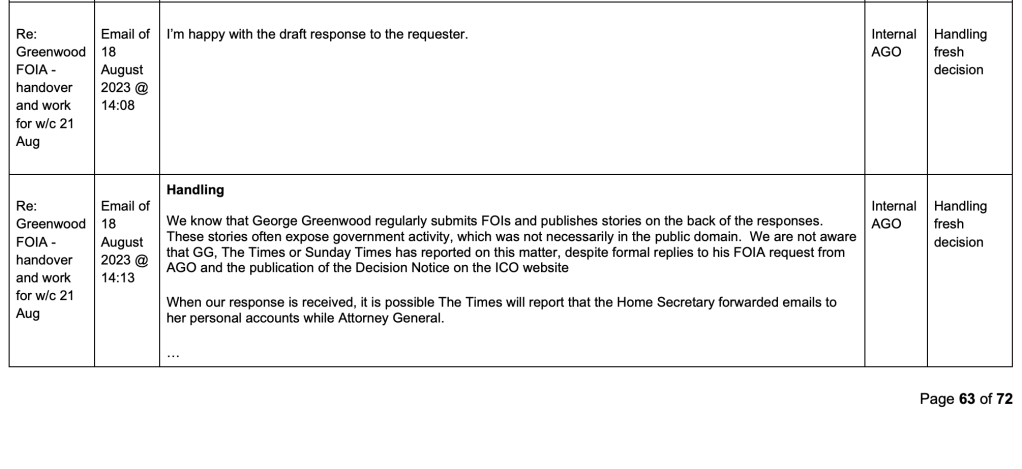

When my SAR came back, it is clear I was immediately flagged as a journalist as soon as I made the request.

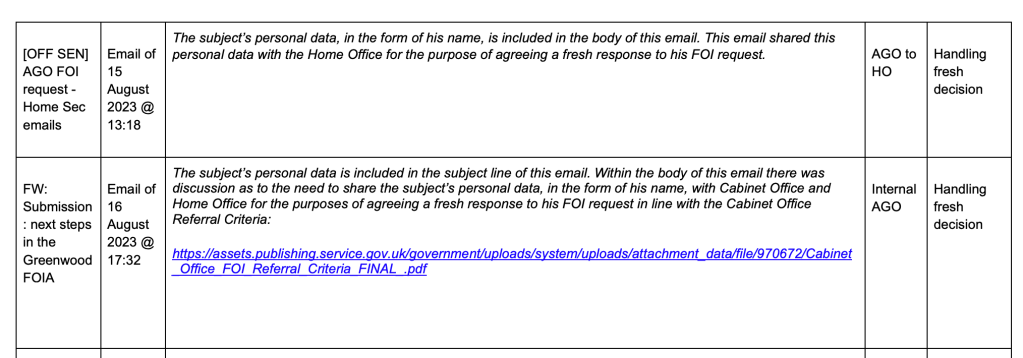

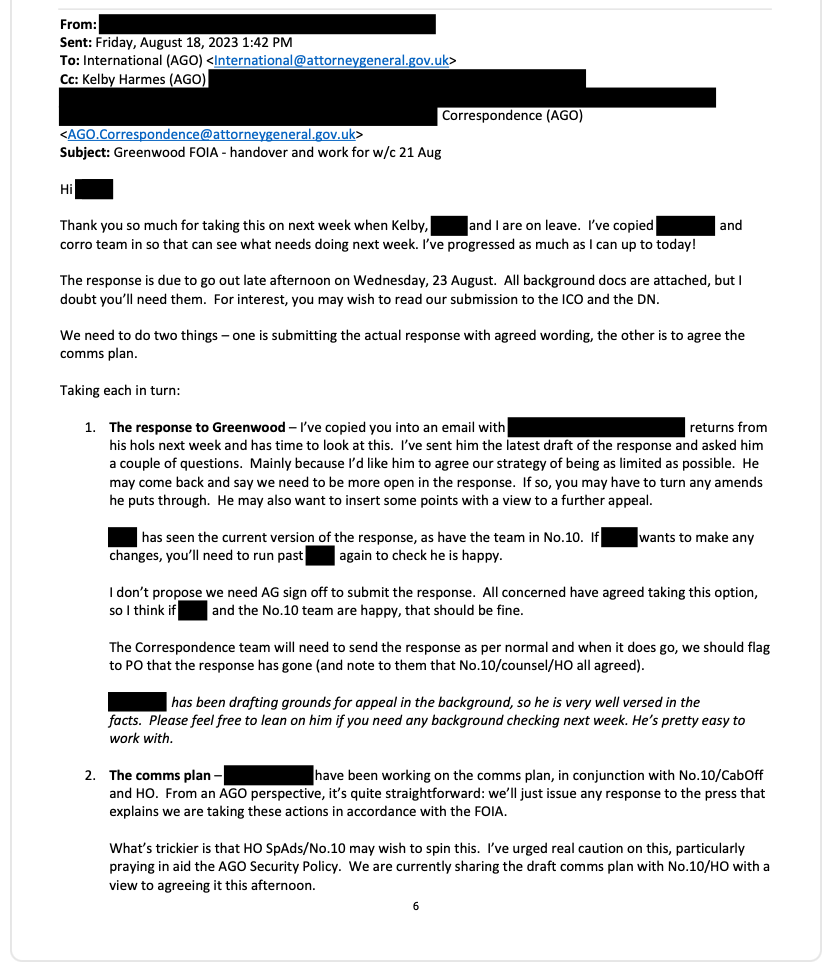

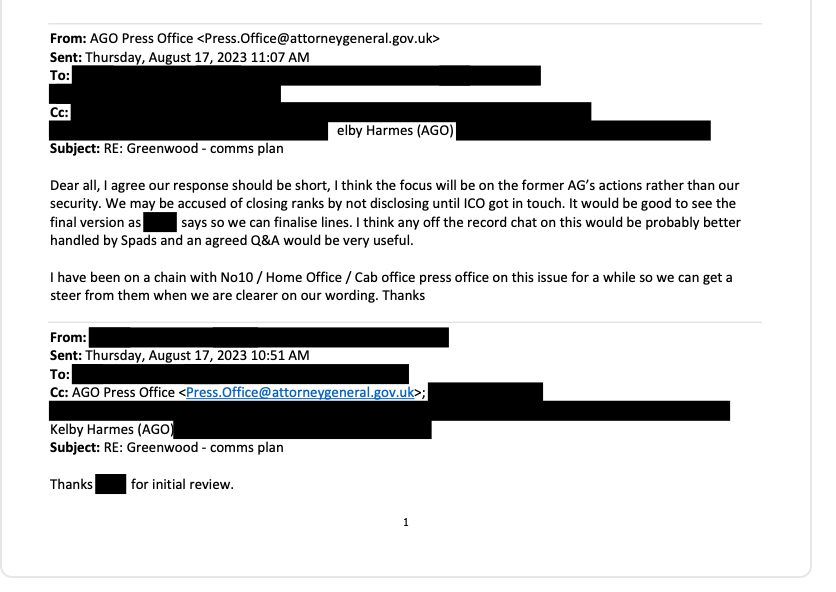

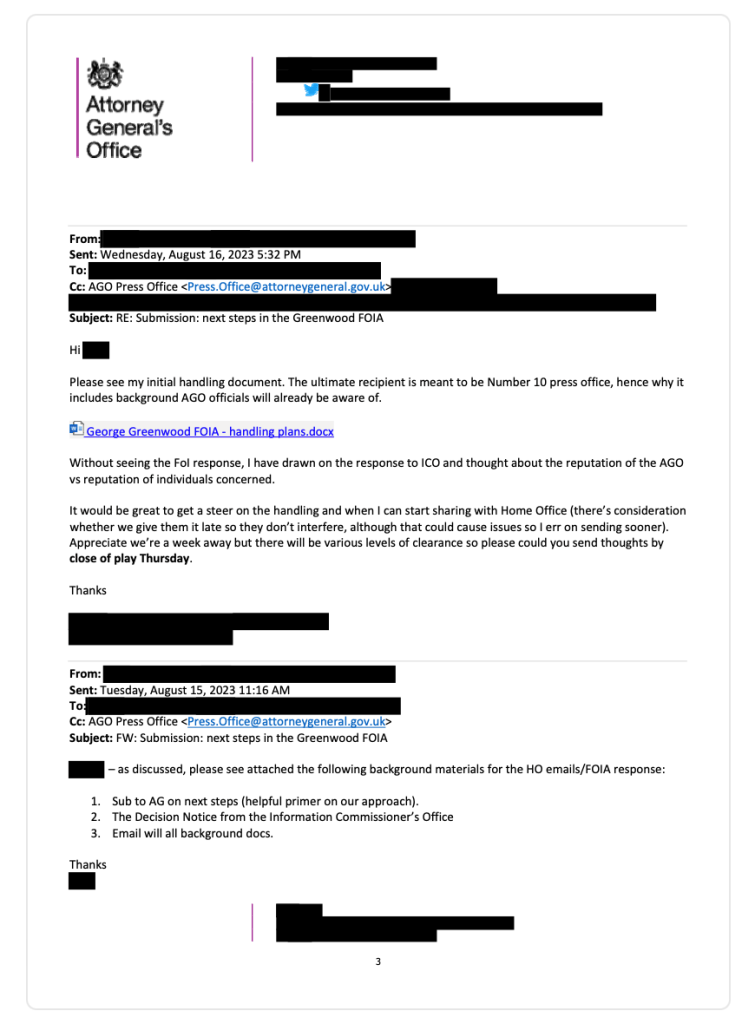

But more unexpectedly, the SAR showed the request was being extensively flagged to both the Cabinet Office and Home Office.

Most surprisingly, it even turned out the department appeared to have prepared a document called “George Greenwood FOIA handling plans”, which it provided in heavily redacted form, as well as the below summary of my career.

Normally, I don’t follow up on SARs with further requests.

The material released normally provides enough to show if a request may have been resisted for reasons it shouldn’t have been which is useful as a line for the eventual story and for the wider issue of showing shortcomings in how departments handle requests.

But the 72 pages of SAR disclosure, about what was ultimately a request for a single number, left me concerned. I wanted to see the wider context in which the discussions around my request had taken place.

So I filed a further request, an FOI for a copy of the email chains in which my personal information had sat.

“Fundamentally improper use of FOI”

The AGO was not keen on this material being disclosed.

It refused this request, claiming my request was “a fundamentally improper use of FOI”.

The ICO gave this argument short shrift in a decision notice, finding the AGO had failed to adequately consider my arguments as to why there was value in the disclosure to hold the AGO to account on its FOI procedure.

When disclosure came, the reasons for their reluctance became clear. I was sent hundreds of pages of discussion between the Home Office, AGO, Cabinet Office and Number 10, about my request.

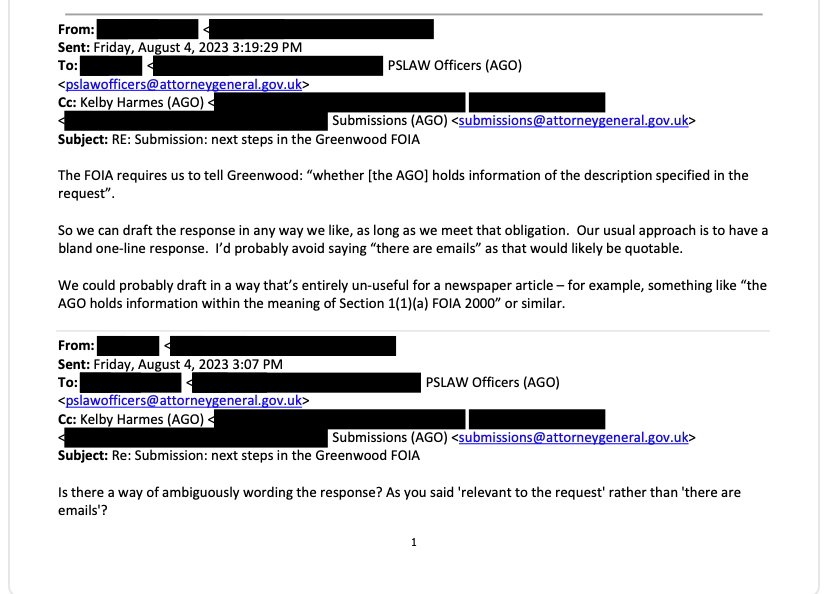

There appears to have been an attempt to make the first response the AGO was forced to make, confirming that Braverman had used private emails as AG, as bland as possible.

One departmental press officer wanted to “look more into Greenwood” and asked for “intel” on me.

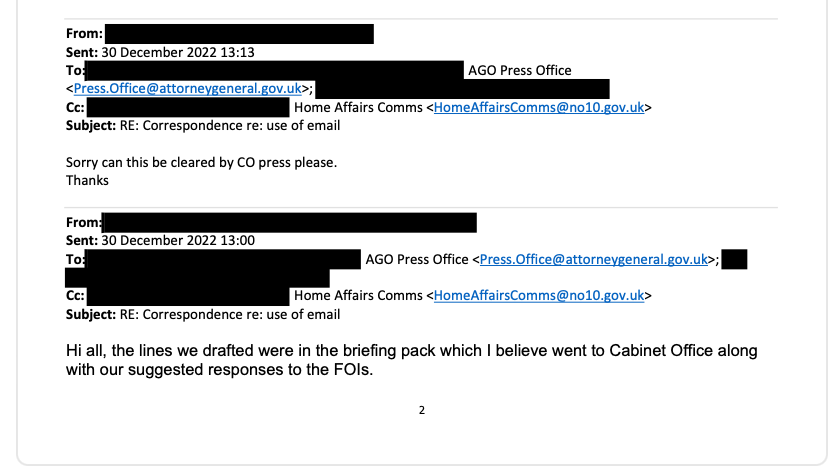

It is clear AGO officials felt unable to do anything without Cabinet Office clearance.

So many cooks clearly slowed things down.

The involvement of special advisers in the FOI process, for which there is no need, has been criticised by the ICO in its recent practice recommendations as something that was unacceptably delaying disclosure.

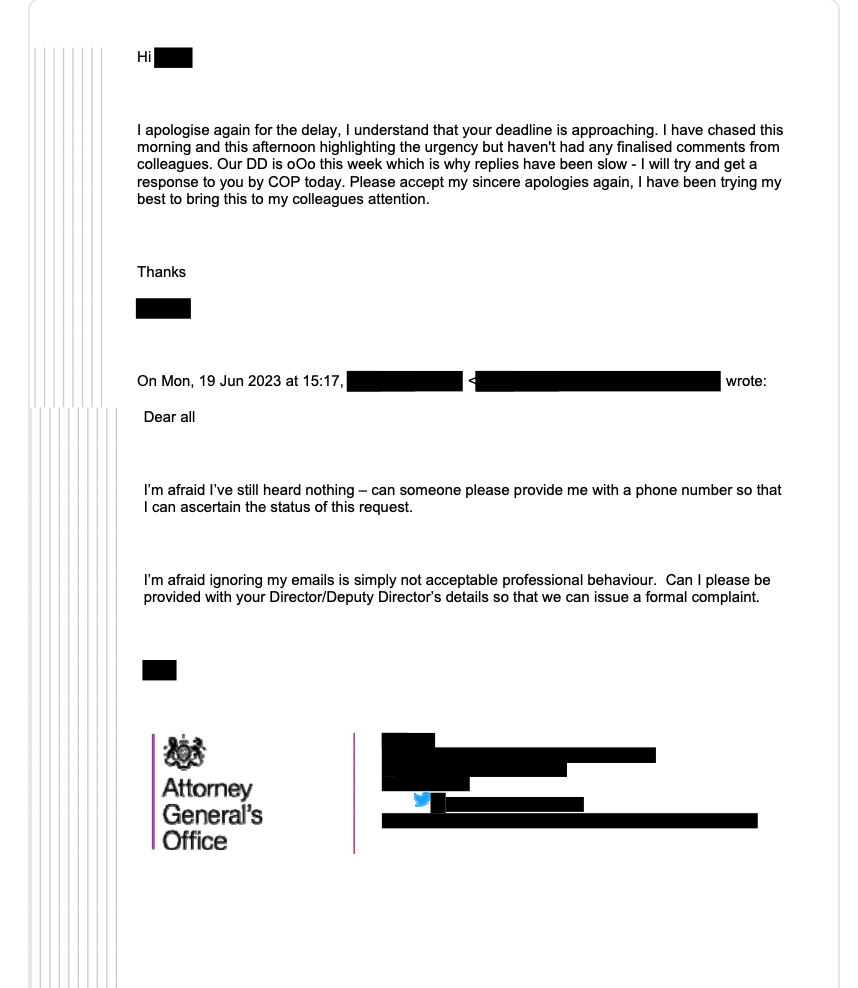

This led to tensions between departments…

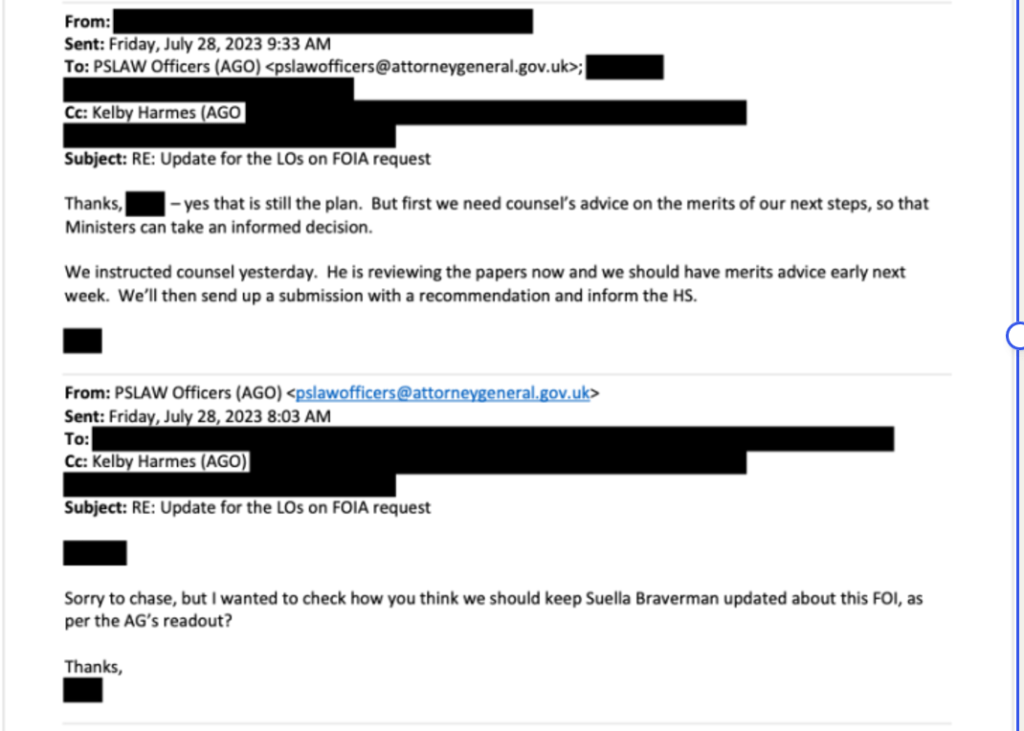

Braverman’s office appears to have been kept in the loop on progress with this request.

The department sought the advice of both of its ministers, the Attorney General and the Solicitor General, on the request.

The AGO itself was clearly worried about being caught in intergovernmental battles over the disclosure, including on how different offices spun the results.

And finally, the meta-request revealed a full copy of the backgrounder on me and my request that was circulated around government as they prepared their response.

As I have commented on before, beyond additional internal pressure to push back on disclosures, the practical issue such special attention brings is to slow down the process.

It is clear from the documents, and from other disclosures I have received in the past, that a “sighting in” of special advisers and ministers in the FOI process is treated by officials in practice as a barrier than must be crossed before disclosure can be made, and isn’t just a heads up.

There are also questions to be asked about the waste of public time and money for all involved by government resisting legitimate requests for disclosure, rather than simply releasing the material in the first place where the public interest is obvious.

It is not clear why so many government ministers and numerous officials became so involved in the handling of a request, where FOI professionals are employed to do exactly this in government.

While I was still able to report on this case, I only received the full picture after Braverman had left office (the ICO also wrongly refused my request for the exact numbers, which forced me to make a tribunal appeal).

This kind of delay waters down the value of an important constitutional right, makes the job of reporters and others seeking to shed light on government harder, and ultimately undermines trust in government.

If the ICO, charged with improving the operation of FOIA, wants to be truly effective, it needs to start cracking down on requests being handled in this way, using the powers it has more aggressively, and taking a much more sceptical view of government arguments.

It is frustrating when ministers espouse the importance of press freedom and freedom of speech in public, but when it comes to the handling of the freedom of information act, seem to take such a different approach.

I asked the AGO if they wanted to comment on the issues raised by these disclosures. The department declined to do so.

Photo credit: Home Office

Leave a comment