Last year, as was widely reported, Boris Johnson took a sojourn to Venezuela for talks with its autocratic leader, Nicolas Maduro.

He later received a ticking off from regulator ACOBA for “failing to clarify” his relationship with the hedge fund that set up the trip.

Controversy also arose around how much the Foreign Office knew about the visit.

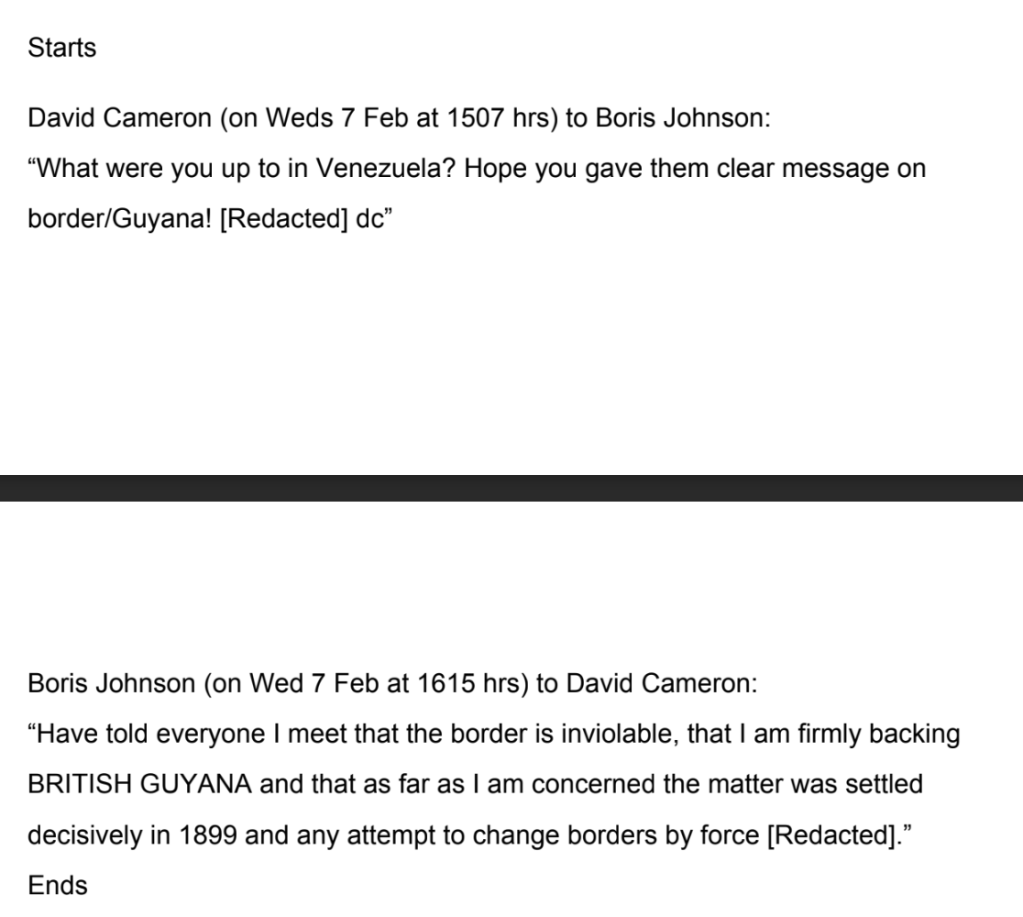

The department briefed that Johnson had been in contact with the then foreign secretary, David Cameron, to discuss it, including via text.

Knowing this would be disclosable, I duly filed an FOI request.

The pair had been political rivals since their time in the Bullingdon Club drinking society at Oxford, so I was curious about whether that rivalry had carried through in their private correspondence after both had been prime minister.

As is depressingly familiar, the FCDO issued a knee-jerk refusal, citing potential harm to international relations and upheld this position on review.

The ICO gave this short shrift, forcing them to disclose most of the message during its investigation.

This revealed interesting, but fairly routine, discussion of the trip.

The only part removed likely related to Johnson’s view of what the UK might do if Venezuela tried to compromise the border – a removal which may not be unreasonable.

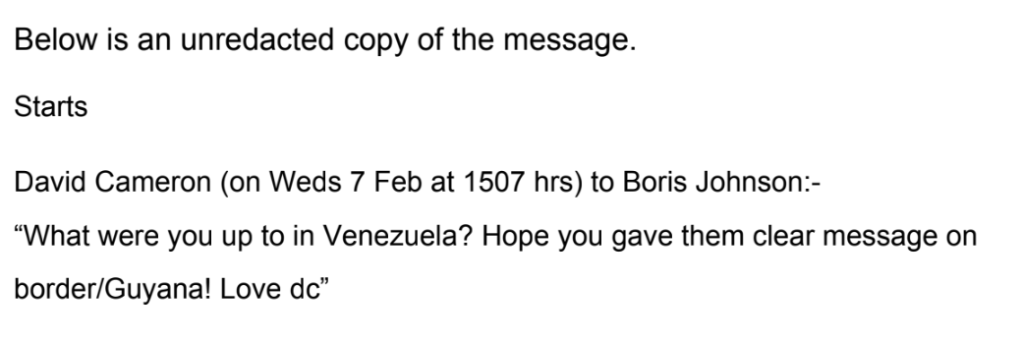

One redaction intrigued me, however. A single word in David Cameron’s response was redacted under section 40 (personal information).

This was bizarre. This exemption normally covers information such as people’s names and identifying information about themselves, and does not cover the professional affairs of those in public life.

As foreign secretary and former prime minister, the only matters Cameron could reasonably expect to have redacted would be highly sensitive material such as health information.

The FCDO wouldn’t budge, so the case went to a decision notice, in which the ICO ordered this to be released.

The word? Love.

Time does appear to heal all wounds.

It turned out that the FCDO had forced the ICO to spend the resources in issuing a formal decision notice, as well as delaying a final response by two and a half months, because it was trying to redact a mildly amusing use of a term of endearment between two former political rivals.

This kind of knee jerk refusal frustrates FOI users and the ICO alike, a redaction with no prospect of being upheld, but which gums up the process.

Departments are quick to use section 40 in this way, even where the subject of the request is clearly a public figure, who cannot possibly expect professional matters to be exempt on privacy grounds.

The ICO previously had to overturn a decision by the Department for Education to withhold information about Lord Wharton of Yarm on data protection grounds.

The eventual disclosure allowed me to report that he had interviewed the wife of his close ally, Tees Valley mayor Ben Houchen, for a job at the education quango he chaired without listing in his written declaration of interests multiple donations he made to her husband.

However, the ICO itself has a mixed record on this.

It declined to uphold an appeal I made about a Labour MP’s lobbying activity after they had lost their seat in 2019 but regained it in 2024.

The ICO argued that in their five years out of office, the now MP had a reasonable expectation of privacy.

That doesn’t seem right, given the importance of holding MPs accountable, and I’ve had to appeal this one to the First-Tier Tribunal.

Privacy is important, but the overzealous use of the privacy exemptions over the professional affairs of public figures can only have a chilling effect on journalism.

Photo credit: Andrew Parsons

Leave a comment