Rights are only rights when they come with a mechanism of enforcement. Otherwise, they are just pretty words.

If ones tries leaving a restaurant without settling the bill one will quickly find out about how property rights are enforced.

Traditionally, FOI requests have not faced issues with enforcement.

If a government department holds a document and the transparency regulator orders its release, not doing this would be treated as contempt of court.

Even the most recalcitrant departments are unlikely to risk what would follow from that.

Government by WhatsApp

But what happens when disclosure is ordered of a document which is not physically in government hands?

There is a growing issue in government of a disappearing paper trail, as WhatsApp and private email usage in departments becomes endemic.

Key decisions are often discussed extensively in private chats.

Records setting out how decisions were made which previously would have been properly documented in an email chain or letters are now not always passed back to departments.

This risks a serious democratic deficit, and if things go wrong, can frustrate proper accountability.

The law on what is subject to FOI is very clear. This was confirmed in a case I fought last year trying to get hold of copies of former health secretary Matt Hancock and his lover Gina Coladangelo’s WhatsApp messages about government business.

It doesn’t matter if records are held in personal email or WhatsApp accounts, if they constitute official business, they are disclosable.

In that case, the messages had been provided to the department, likely as part of the Covid Inquiry process, and were disclosed.

Beyond some entertaining quips, these did not shed considerably new light.

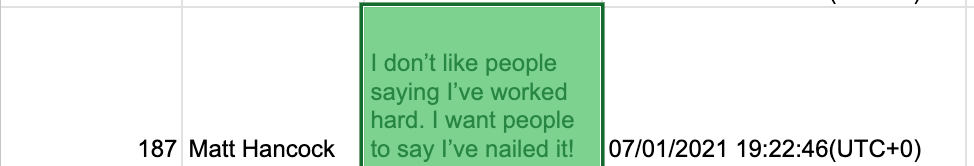

Hancock said of his pandemic performance that “I don’t like people saying I’ve worked hard. I want people to say I’ve nailed it!”, talked about “terrible” photos him used in the press, and described Rishi Sunak’s infamous hospitality recovery subsidy as “eat out to infect out”.

But I have been pursuing another case, in part to try and help clarify what happens when FOI requests are made for information only now held by a private individual.

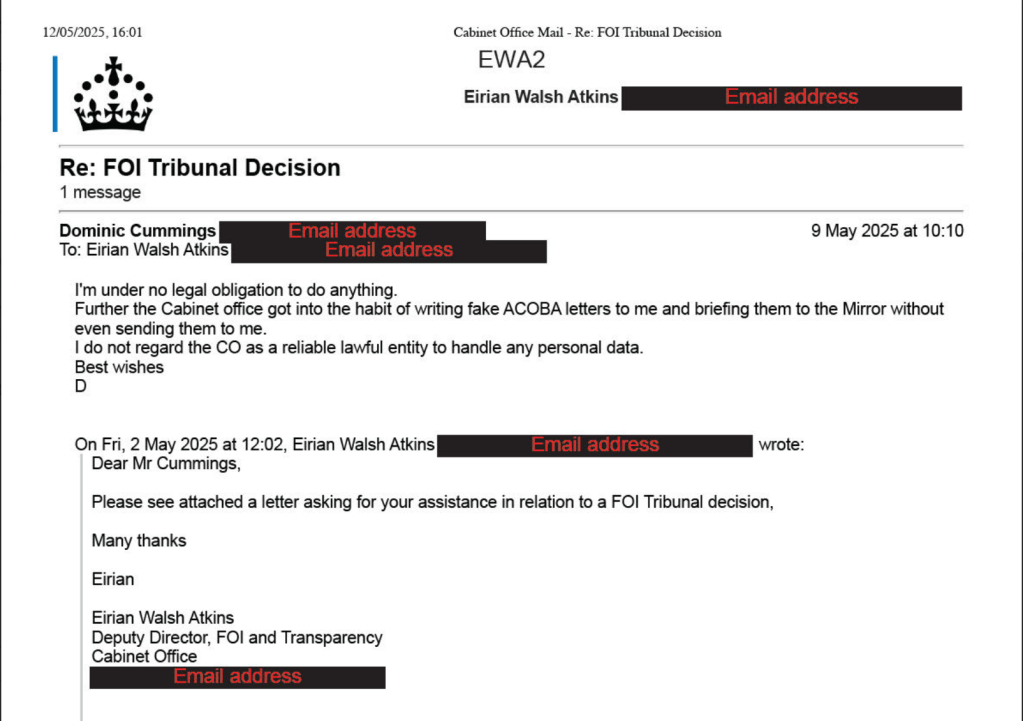

I got my answer in a characteristically diplomatically worded email from Dominic Cummings.

Five years later…

Turn your minds back to the year 2020.

Dominic Cummings had just been found to have taken a trip to Barnard Castle in Durham during lockdown whilst likely having the virus, which caused widespread outrage.

I had wanted to see what Cummings had been discussing with his fellow advisers how best to handle the political fallout of the situation, and to see if that differed from the public statements he had given.

So I filed an FOI.

What followed is the longest single appeal process I have had the pleasure of dealing with.

The Cabinet Office refused the request, saying it would be too expensive to respond to, and upheld this appeal on review.

I appealed this to the transparency regulator, the Information Commissioner, in October 2020.

An unreasonable email

At this point, under the previous commissioner, the regulator was simply failing to deal with a backlog of appeals that had built up over the pandemic, significantly undermining the public right to know.

It took two years for the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) to issue a decision in October 2022, saying the Cabinet Office had not properly searched its records.

The Cabinet Office refused the request again, saying the information was Cummings’s personal information. It later added a claim that disclosure would “prejudice the conduct of public affairs” by discouraging internal discussion on how best to handle press inquiries.

In August 2023, the ICO upheld the Cabinet Office’s position. I appealed this case to the information tribunal, pointing out at no point did anyone appear to have actually attempted to ask Cumming’s to search his records.

The Cabinet Office continued to argue in the tribunal case, through taxpayer funded barristers, that sending Dominic Cummings an email asking him to conduct a search for any messages he might still have “as they did not consider this to be an exceptional circumstance.”

Delays in the tribunal system meant that it took until April 2025, almost five years after the original request for filed, for the tribunal to rule.

It found that the Cabinet Office had wrongly failed to ask Dominic Cummings to search his messages.

Judge Watkin ruled that “It is not appropriate for the CO not to have approached Mr Cummings … to request that they provide any relevant information that they may hold in circumstances where it would appear that information otherwise belonging to the CO may have been retained,” and ordered the Cabinet Office to do so.

The result of this was that around five years after it should have done so, the Cabinet Office emailed Dominic Cummings asking him to check his phone for any messages related to the request.

This was Cummings’ response.

Cummings’ email clearly sets out the problem that permitting the use of private platforms in government poses when you suddenly need those records again.

What can you actually do when the person has left government, and declines to engage with the process?

Cummings has not been a state employee for several years and is likely no longer subject to any current contractual requirements to assist officials with these kinds of cases.

Even if he was, it seems unlikely the Cabinet Office would open a breach of contract case against him to enforce a request it clearly didn’t want to answer in the first place.

Given the passage of time, it is not clear how the department could be forced to do this unwillingly, or whether this case would even succeed.

No obvious route of action

In his decision, Judge Watkin states that “my remedy would be to complain to the Information Commissioner”.

But it is not clear what powers the ICO would have to enforce in this case either. If a public body refuses to disclose a record despite an order by the ICO to do so, it can certify this as contempt of court.

But in this case, despite its pretty egregious foot dragging, it is hard to argue that the Cabinet Office is now in contempt, given that it has explicitly asked Cummings to search for the records after the direction of the court.

Even if it had some sort of theoretical route of action, the Commissioner might choose to exercise his discretion not to do this, arguing that the records likely no longer exist or they would be unduly burdensome to retrieve given the passage of time and their relative value.

So, what then? We appear to be in a situation where a right has been created with no actual means of enforcing that right.

This is a clear loophole in the law that would probably need some sort of legislation to properly close.

And this does not even get into the thorny issue of auto-deleting messages.

Any journalist who contacts politicians or their advisors can see for themselves use of this is widespread in Whitehall

While it is an offence to delete information which has been explicitly requested under FOIA and that a requestor would have been entitled to, if a record is deleted before it is requested, there is no offence, so nothing that can be really enforced against through the FOIA regime.

It is clear without an overhaul of the legislation, those who wish to govern in secret by taking things offline will be empowered, knowing that even if FOIA creates a theoretical right to their correspondence, that this right is just pretty words when they leave public office.

Though there are those who might criticise Cummings here for his attitude. In his defence he has submitted a lot of material from private channels to the Covid inquiry.

I should also say he did not oppose my application to publish this email from the Cabinet Office’s witness statement, where without the consent of all parties, it would have required a judicial order, and for which I am grateful.

Whitehall arms race

I asked him why he had declined to assist the Cabinet Office.

He told me that “actually I have no data to hand over, but I was curious what would happen if I refused to engage with the CO.”

He alleged that “much of the CO behaves like a drunk mafia now – they got into the habit of writing fake letters to me and briefing them to the Mirror without even sending them to me. So I was not inclined to help them.”

He felt that the rise of private messaging in government was at least in part due to a kind of arms race between officials and political appointees.

He claimed that “I’m sure you’re aware the civil service set up a private messaging system for them to organise things with messages that auto delete and they regard as outside the scope of FOI – while they leak emails from official accounts of ministers and spads – which sums up a lot about modern Whitehall.”

“The lack of ethical standards means spads & ministers inevitably & logically do not have confidence in official systems so they also use unofficial methods to avoid being spied/leaked…”

The Cabinet Office declined to comment.

Picture credit: Ian Britton/Flickr

Leave a reply to From FOI blog to formal regulatory rebuke: The case of the former Attorney General’s emails – Relight My FOIA Cancel reply